When the U.S. Treasury announced coordinated sanctions this month against a network of casinos and restaurants stretching from Mexico to Poland, the move seemed at first glance another step in Washington’s long war on drug cartels. But behind the bureaucratic language of designations and enforcement lies a story that reveals something deeper: how globalized finance, weak regulation, and fragmented sovereignty have created the perfect ecosystem for organized crime to evolve into a borderless business empire.

At the center of this new criminal geography stands an unlikely figure — Luftar Hysa, an Albanian-born businessman who divides his time between Mexico, Canada, and Europe. The Treasury describes him and his family as the Hysa Organized Crime Group (HOCG), a transnational syndicate that launders millions of dollars in proceeds from the Sinaloa Cartel, the world’s most powerful drug-trafficking organization.

A Transatlantic Alliance

The Hysa network’s activities, detailed by U.S., Mexican, and Canadian authorities, illustrate how Balkan criminal groups have integrated themselves into Latin America’s narcotics economy. The alleged partnership between the Hysas and Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada García, Sinaloa’s aging patriarch, reflects a division of labor familiar to global capitalism itself: Mexican cartels generate the product, while Balkan intermediaries move and recycle the profits through opaque financial circuits.

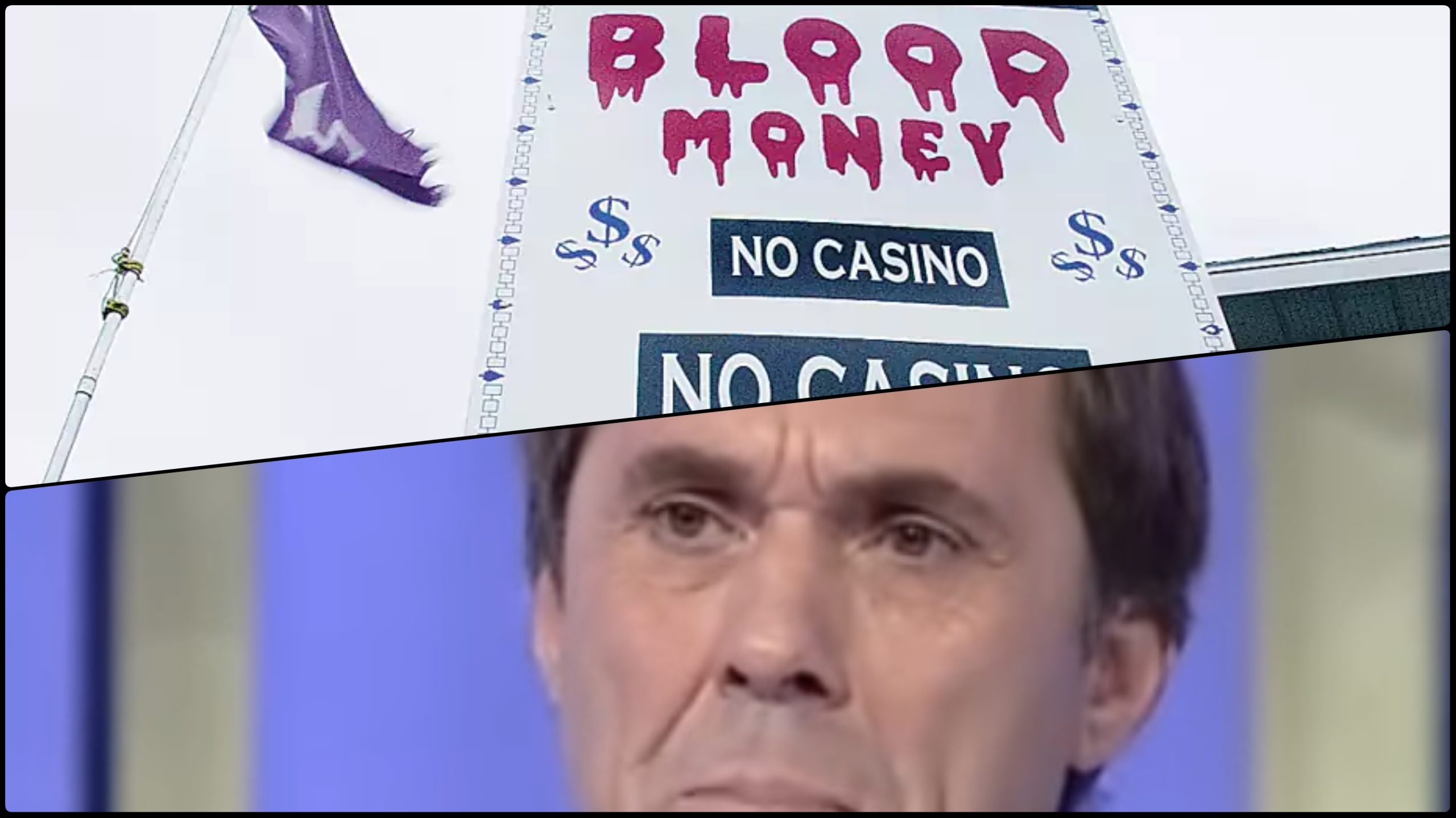

According to the U.S. Treasury, the Hysa Group used casinos, restaurants, and logistics companies in Mexico and Canada to launder drug proceeds. The family’s reach extended to Europe, where it allegedly used shell companies in Poland and Albania to reinvest illicit funds in tourism and real estate. OFAC’s new sanctions freeze the group’s assets in the United States and bar Americans from any dealings with its businesses.

In parallel, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) proposed cutting ten Mexican gambling establishments — among them the Midas, Skampa, and Palermo casinos — from access to the U.S. banking system, citing their central role in money laundering for the Sinaloa cartel.

The Canadian Front

Far from the deserts of Sinaloa, a quieter operation was unfolding on the outskirts of Montreal. In October 2023, the Canadian newspaper La Presse revealed that the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) suspected Hysa of using the Magic Palace Casino in the Mohawk reserve of Kahnawake to launder drug money.

According to court filings, investigators believe Hysa “infiltrated the Kahnawake reserve to facilitate money-laundering activities on behalf of the Sinaloa Cartel.” Canada’s financial intelligence agency, FINTRAC, identified more than 50 suspicious transactions involving Hysa and his businesses, including C$28 million in transfers from a restaurant he owns in the casino complex.

That a Balkan figure could exploit a semi-autonomous Indigenous territory in Canada to move Mexican drug profits shows how globalization has blurred the traditional boundaries of law enforcement and sovereignty. The Kahnawake Gaming Commission operates outside Quebec’s legal framework, regulating its own casinos even as provincial authorities deem such operations illegal.

From Tirana to Tijuana

The Hysa case sheds light on an emerging pattern in transnational organized crime. Over the past decade, Balkan groups have moved beyond the role of drug couriers or enforcers. They have become financial engineers, using their knowledge of offshore structures and weak regulatory regimes to provide laundering and logistics services for Latin American cartels.

In return, they gain access to a global criminal economy that spans continents — from cocaine shipments routed through Adriatic ports to cash washed through real estate in Canada and the Caribbean. The convergence of these networks mirrors the same economic logic that binds global trade: specialization, efficiency, and diversification of risk.

Governments on the Defensive

For policymakers in Washington, Ottawa, and Mexico City, the Hysa case underscores a growing dilemma. Traditional tools of enforcement — asset freezes, indictments, and targeted sanctions — struggle to keep pace with an economy of crime that is as nimble as any multinational corporation.

Sanctions, while symbolically powerful, can only disrupt flows temporarily. The networks adapt, rebrand, and reappear under new fronts. The persistence of casino-based laundering operations in Mexico and Canada highlights the limits of compliance regimes when political will and local jurisdiction collide.

Yet the joint U.S.-Mexico action marks a shift toward more coordinated, systemic responses. By linking financial intelligence with law enforcement, it signals an acknowledgment that fighting cartels today requires dismantling their financial infrastructure, not merely interdicting their shipments.

A Window into the Future

The saga of the Hysa network may be a preview of what organized crime looks like in the next decade — borderless, digitally sophisticated, and embedded within legitimate economies.

In this emerging order, the geography of crime no longer maps neatly onto the geography of sovereignty. A casino in Kahnawake, a company in Warsaw, a restaurant in Mazatlán, and an offshore account in Tirana can form a single circuit of illicit finance.

The global economy’s openness — once a hallmark of progress — has also given rise to a new criminal elite that thrives in its shadows. The battle against such networks will depend less on spectacular arrests and more on building transparency across the financial system.

For now, the joint sanctions on the Hysa Group represent a warning shot. But without deeper reforms in how countries regulate finance, the world’s next generation of cartels may look less like armed gangs — and more like multinational investment firms.