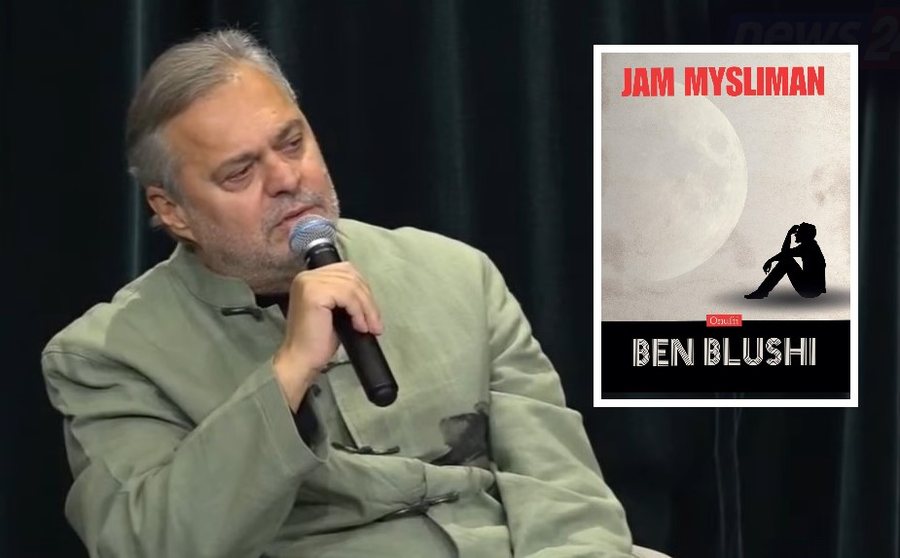

Ben Blushi, Albania’s veteran politician, journalist, and author, has long sought to carve a space for himself in the literary world. His latest book, I Am Muslim, has reignited discussions about his role as both a public intellectual and a literary figure. Yet, as much as Blushi might aspire to emulate the global stature of Salman Rushdie, the realities of context, culture, and history set unavoidable limits.

Blushi often positions himself as a provocateur, emphasizing in interviews that critics have labeled him as such. “They’ve pinned this tag on me,” he insists, almost ritualistically, in media appearances. Yet, unlike Rushdie, Blushi is not a writer whose words have stirred global controversies or drawn threats to his life. He is a provocateur in the Albanian context at most, navigating a society where literature competes with politics, media noise, and everyday pragmatism.

In interviews, Blushi draws parallels to global figures, like the Indian villagers he mentions when discussing the spread of technology. He could have spoken of rural Albania, yet he turns to India, perhaps unconsciously echoing his admiration for Rushdie — the Muslim-born author who achieved international fame by challenging religious orthodoxies and expanding literary boundaries.

But the differences are stark. Rushdie’s upbringing in colonial India, his status as a minority within a majority Hindu society, and the geopolitical currents that amplified his work, created a platform few writers could replicate. Blushi, by contrast, was born in post-communist Albania, a small nation where literary output seldom commands global attention or intervention from powerful states. His society’s tolerance further insulates him from the kind of existential risks that shaped Rushdie’s notoriety.

Literarily, the gap is equally significant. Rushdie created worlds where history, mythology, and fantasy intertwined to probe universal human experiences, pushing the limits of language and imagination. Blushi, though competent and readable, works largely within Albanian realities — stories rooted in local history and society. His novels, such as Otello, the Moor of Vlora and KM Prime Minister, offer vivid portrayals of Albanian life but do not aspire to the transformative scope of Rushdie’s universe.

Moreover, while Rushdie’s defiance made him a global symbol of free expression, Blushi navigates literature with a practical eye on politics and media. His writing is intertwined with public life, serving multiple purposes but never confronting existential threats. His style is linear, narrative-driven, and accessible, lacking the radical linguistic experimentation that marks world-class literary influence.

In short, Ben Blushi is a product of Albanian realities — talented, articulate, and ambitious, yet constrained by the local context. His aspiration to be a Rushdie-like figure is understandable but inevitably limited by history, geography, and the global cultural landscape. He is, as the Albanian observation goes, a “Ben” rather than a “Salman” — a writer whose work resonates locally, reflects national concerns, and provokes discussion, but does not yet alter the course of world literature.

Yet within Albania, Blushi remains significant: a voice navigating the intersections of politics, journalism, and literature, shaping public discourse and chronicling the Albanian experience. His works, flawed or brilliant, are a testament to a society in dialogue with itself — and to a writer aware that talent alone does not make a literary legend.